Interviews

An Interview with Science Woman

J. Robert Lennon

Teacup Literary Magazine

Volume 2, Number 1

Missoula, Montana

Science Woman’s laboratory is in the corner apartment of Missoula’s Brunswick Building, a former railroad hotel that today serves as studio space for artists and writers. Freight trains still run nearby, and their sounds filled the room as we spoke. As we sat down, Science Woman poured me a cup of hot, brown liquid from the complicated series of glass tubes and beakers that make up her experimental apparatus. Only when she offered me a buttered scone did I realize the liquid was tea – and very good tea, at that. While we spoke, Science Woman wore her trademark white lab coat and leopard tights, along with a pair of cat-eye glasses and a pocketful of pens.

LENNON: You seem to have a thing about tea. Can you talk about that?

SCIENCE WOMAN: My family origin is basically British, and tea drinking has been a long tradition in that country. My mother drinks tea with milk and it was served at home, so I probably started drinking it pretty young, and liking the flavor. Also, when I was a child my family lived in Iran, which was pretty well settled by the British at various points, so tea was there, was something I associate with my childhood. It’s sort of warm and soothing, and as an adult, I’ve come to appreciate its qualities of mental alertness, which I think it has without being as dominant or aggressive as coffee.

LENNON: So you think it enhances the creative process?

SCIENCE WOMAN: For me, there’s probably a relationship, although I haven’t tested it to find out. My guess is (without a controlled experiment) that it has a positive effect. I had a birthday party about 10 years ago, a tea party for my women friends. I made the mistake of offering coffee as an alternative, and no one besides me drank tea. I was terribly disappointed. And so the next year, I invited the same people, and would not offer coffee. There was no coffee in the house. I insisted they had to drink tea – it was my birthday, and they had to celebrate it the way I wanted to. And they had a great time – they were converted!

LENNON: Let me move on to a broader question. Many people believe art is the exclusive domain of emotion, while science is purely rational. You, however, are both an artist and a scientist. How would you respond to these stereotypes?

SCIENCE WOMAN: My father was a chemical engineer, so I grew up in a household with a scientist. My mother’s mother was an artist; my father’s grandfather was an artist. And so there’s a tradition of scientists and artists on both sides of the family. When I was sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, I was doing art on my own, but I was also excelling in science in high school. I was very interested in the early stages of genetic research, so when I went to Mount Holyoke College in 1968, I wasn’t clear if I would end up my four years there as an artist or a geneticist. So I fabricated this major – at this point it’s kind of commonplace, but this was in 1969 – an interdepartmental major between art and what ended up being botany.

The scientists thought it was great that I was doing the science, but they thought the artists were out to lunch. It was a joke – they could not take the art seriously. They thought what they were doing was more important than what the other departments were doing: very dedicated people that worked in groups. And in the art department, they were running around, doing crazy things, also convinced that what they were doing was the most important thing, but a lot more fun.

I felt like I had to make a choice. If I continued with science, I would have to go into a master’s and a PhD program, work with large groups of people, be funded through corporations and schools. Art provided more opportunity for what I would call independent research. If I was drawing a cell, and I wanted to elaborate, I could do that in the arts, but in science it would have been frowned upon. So I basically rejected the science by the time I graduated.

I moved to Montana in 1972, started working on my own, kind of developing, very slowly, a clientele and a personality, the whole thing: a career. And in 1982, an artist named Mel Watkin was having an exhibit in Great Falls, at Paris Gibson Square (Art Museum), and (my husband) Max and I drove up there and saw what she had done: she had taken over the corridor – it’s in this big, old school building – and had made characters out of cardboard and different things, in this setting that she had created. And after I walked through, I knew I was Science Woman. Science Woman appeared. I think it triggered something in me, away from the sciences, away from other people telling me what to do. It allowed me to reapproach the sciences on my own terms. So, in 1982 I did the very first painting of Science Woman. I didn’t do any personal appearances – it never occurred to me to dress up and be Science Woman, at that point.

LENNON: And when did that begin?

SCIENCE WOMAN: That started about six years ago, in response to a request to appear at a celebrity fund-raiser. They asked people who were kind of prominent in the community, and they asked me as Leslie Van Stavern Millar, artist. I didn’t feel comfortable appearing that way, and so I dressed up as Science Woman. I baked a cake, and it had small signs on popsicle sticks with admonitions telling you what to do – blow up your TV, read books to your children, etc. – because that’s one of the characteristics of Science Woman: she has such authority, she can tell you what to do.

But back to your question: I would say, now that I’m older, and I’ve been out of school for nearly twenty-five years, I can see that there’s a lot of crossover, that scientists do, in fact, have a sense of humor, that artists can be very scientific in the way that they work. It’s given me more appreciation for the complexity of people.

LENNON: There’s something you mentioned a little while ago, about your interest in genetics. That reminds me of the “authority” of Science Woman. I recently read about a twin study that strongly suggested genetics had much more control over us than was previously thought. How does that idea fit into your work?

SCIENCE WOMAN: Was that in the New Yorker?

LENNON: Yes.

SCIENCE WOMAN: I found that really fascinating, because for twenty or twenty-five years I’ve been thinking about nature versus nurture – genetic heritage versus your cultural and environmental situation. Reading that article was kind of startling to me, because I tended to give more credence to upbringing. It re-interested me in evolutionary psychology, or how the genes determine how humans operate, on a very subconscious level. And that was something I was interested in twenty-five years ago, and nobody was talking about it at the school I went to!

LENNON: Despite increasing equality between the sexes, science still seems to be dominated by men. Did you feel any effect from that in school, and did it affect your attitudes toward science or art?

SCIENCE WOMAN: I would say that’s not true in my circumstances, because when I entered Mount Holyoke in 1968, the men’s schools weren’t admitting women and drawing away some of the more talented ones. At that time, if you were a talented woman with a possible interest in science, you went to one of the women’s colleges. Mount Holyoke was “kick-butt” in the sciences – if you were going to be a doctor, it was a good place to go.

I did run into a few friends in the biology and chemistry fields who had problems getting into graduate schools. When they left Mount Holyoke, which was a supportive science environment, the transition to the bigger world was not so easy, because of prevailing attitudes. But one woman I know who was having a hard time got so angry that she wrote Harvard, and all these schools who had turned her down – she was a stellar student – and told them she thought they were being prejudiced against her, and that she was every bit as qualified as the guys they were accepting, and they turned around and they accepted her. So I saw someone challenge that and succeed.

In fact, now that I am Science Woman, I’m a member of the NWS, an organization for women scientists. There are a lot of talented women out there. I guess I feel optimistic about it. In fact, I think it was harder at that time as a woman entering the arts world – it had been dominated by men forever and it hasn’t been overthrown.

LENNON: Let me ask you about your Science Woman performance. Unlike many artists, you come into close personal contact with your audience. Does this enhance the art-making process?

SCIENCE WOMAN: I don’t know that by meeting my audience, it’s changing the way I do my art. I think the art is coming from a place inside me that isn’t particularly affected by where it’s going to go.

I do think it’s changed the way I feel about presenting my work, and that dialog between the artist and the art and the viewer – that has changed dramatically, and in a really positive way. In a sense, the art process has become freer, because I’m more confident that there are interested people, who are intelligent and articulate and see something of value in what I’m doing. And I would say that contact with the audience is very addictive – it has made life difficult for me in some ways.

Typically, you produce a piece of art, you frame it, put it on a pedestal, you put it in the gallery, you go to the opening, which is one night out of a possible two weeks, and that’s it. But with the Caravan Project*, I was talking with virtually everyone who saw my art. It was a really wonderful experience. Now I’m finding that just producing a body of work, putting it out there, selling it – it goes to homes and I may not have a clue where it is – is, in many ways, quite unsatisfactory. So part of what I’m trying to do is figure out how to achieve that interaction, and sell my work and have it be part of the community.

* The Caravan Project was a collaborative effort by 14 visual artists who traveled the state of Montana for six weeks the summer of 1995. The mission of the Caravan Project was to set up portable temporary outdoor art shows in a variety of communities, ranging from Helena to Moccasin. Science Woman was a participating artist, showing her dynamic series of gouache paintings, ”Peepshow Stories.”

LENNON: Well, there are scientists who work all their lives on the same problem.

SCIENCE WOMAN: That may be one of my overlying themes!

LENNON: I noticed that you have some Exxon and Esso pens in your pocket…it reminds me of the fact that your father was a research scientist for industry. Now, many people think of science as practical – it gives us all these miraculous and useful things. But in America, people don’t often think of art as miraculous and useful. Do you think it has as important a use as more tangible endeavors?

SCIENCE WOMAN: Absolutely. I have a children’s art text, probably a junior high text, and I was looking through that about 10 years ago. It went from, you know, cave paintings to about the 1960’s, and I thought, the art is an indicator of the culture at a particular time. Then I went through a history text, a straight history text, and it was all illustrated with art! All paintings and statues and architecturally significant buildings. Here we make such a big deal about science and technological progress, and yet the cultures of five hundred years ago – what do we value from them? We value their art! It’s a shame that, in this country, artists and their contributions are undervalued.

LENNON: I think that in the times you are talking about, art and science were less separate. Da Vinci, of course, was not only an artist and scientist, but both at exactly the same time: much of his art was science, and his science art.

SCIENCE WOMAN: Yes – now, in the sciences, like I said, there’s a kind of prescribed route. If you want to be a scientist, you probably get a bachelor’s, a master’s, maybe a PhD; you work with a group of scientists, you work on recognizable problems, hopefully, if you’re successful, you come up with a product that solves those problems. And society goes: this person is wonderful, they cured AIDS, or this person’s wonderful, they’ve figured out a word processor. There are tangible, concrete results people can look at and say, good!, we appreciate that, we will give you money and status.

In the arts, particularly now, when there’s such a confusion of things going on, to recognize that level of quality you have to be pretty sophisticated. The average person on the street will not be able to walk into a museum and tell you what they think is of value and significant, and what isn’t. It’s much more subjective.

LENNON: You’ve probably heard about Komar and Melamid’s “America’s Most Wanted.” They hired a marketing firm to do a huge survey of Americans, asking them which elements they most liked in a piece of art, and which they most disliked. They found that people liked the color blue, athletes, George Washington and landscapes. The things they didn’t like were ochre and pink, triangles, art that wasn’t realistic. So they took the results and painted the paintings Americans most wanted, and the painting Americans least wanted, and of course one was very pleasant and one was very ugly. But in a sense, the ugly one was more interesting – it was more disturbing! It’s almost like tricking people with their own weapon – using rationality, statistics, to create this strange thing.

SCIENCE WOMAN: Well, yeah – I find it a little disappointing that I’m not going to experience the vast quality of cultural support that I would like to think existed for people in my field. Artists are very dedicated people, for the most part: they’re willing to survive on a lower income than most Americans find suitable. They’re willing to take risks.

I read that Matisse, when he was elderly, was recognized in France as an important painter. And apparently, when people saw him, they would line along the street and clap as he walked by! How wonderful to be doing something for the culture, through his own experience and talent. And he was loved by his population! I don’t see that happening in the U.S.

LENNON: You mentioned artists taking risks. In America, iconoclasm is our historical model, given the way the country was begun, and, in theory, is the activity Americans most admire. In advertising, for instance, one of the main ways people try to sell products is by calling them “wild” or “crazy”, or by implying that you’re a rebel by using them. But in fact, Americans seem to fear revolutionary ideas and actions. There’s a certain complacency that, given our history, you wouldn’t expect.

SCIENCE WOMAN: I think I understand that. That was fine two hundred years ago, when our country came into being: people had very good reasons for bucking the system. Now, we’re a prosperous country, we’re admired by the rest of the world, the status quo is very comfortable for a lot of people. The truth is, most people want to have their house, and their meals, and their family and car and security – yet entertain this image of rebellion.

I don’t think there’s enough dissatisfaction to break out of these molds, for the willingness to take those kinds of risks from security. I think that in nations and empires, there’s a kind of progression. I think we’re past the peak, and there’s a decadent, spiraling-outward motion that is going on, and it’s manifested in chaotic behavior from different sections of the population I think we’re falling apart – the center is starting not to hold.

LENNON: Hearing that makes me get a kind of hubris about art: it’s the only thing that can save us from destroying ourselves!

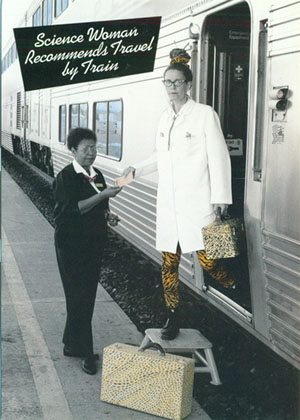

SCIENCE WOMAN: Well, there are things that I am not happy about in society. But my way of approaching that, as Science Woman, is that I have the right to be bossy and express my opinion I’m using my postcards as a means of getting some of that out, some of the things I believe strongly One of the postcards I am working on now is a train image…I’ve been traveling by train for 22, 23 years, and I believe strongly in the train system, and the train system is not being supported by this country. It’s disappointing. We pump all this money into highways, cars, airplanes, and we can’t get it together to maintain a viable rail system. The Europeans have figured it out, the Japanese, the Thai…

Anyway, I was dressed as Science Woman, and I did an interaction with the car attendant of the railroad cars I was getting onto, and we’re printing that as a postcard. The slogan on the front says: “Science WomanRecommends Travel by Train.” And on the back I say that it’s a very civilized form of travel, that I highly recommend it, and that I want like-minded people to write in and put pressure on Congress to support the train system.

LENNON: You know, my wife and I took the train a couple of years ago back east for Christmas: we’re both afraid of flying and we didn’t have a lot of money. And for the first time in many years, I got a great sense of the vastness of America. I think a lot of people don’t comprehend it – when you get on a plane, you step into a little room, and a few hours later you step out. You’re still in America, and it’s still utterly familiar – you can go to a store, get the same products as back home But it’s only by seeing everything, and how long it takes to pass it, that you really get a sense of how…dwarfed we are by the American landscape.

SCIENCE WOMAN: There are a lot of reasons I love train travel, and that is one of them – that sense of place; where I’m really leaving from and where I’m really going to. It’s quite dramatic! I love the opportunity to read, to bring good food with me and indulge my eating habits, that I have a layover in Chicago and can run down to the Art Institute, to the Russian Tea Room for some borscht and Russian tea… and then get back on the train! It also means that when I go east, it’s a big commitment, because the going and the coming back, I’ve spent about four and a half days. I have to consolidate the things that I do.

LENNON: All those days of travel – it’s a vacation in itself.

SCIENCE WOMAN: Right And I understand that I have the luxury of being an artist; I have more control of my time than most people. I’m kind of lucky that way. I also think people could make an effort to include (rail travel) in their plans…or even if they don’t want to, all they have to do is help me put pressure on Congress, so that I can keep taking the train!

LENNON: It does not take four and a half days to send a postcard.

SCIENCE WOMAN: No!

LENNON: What are you working on right now?

SCIENCE WOMAN: The most recent project, which I’ve almost completed, is three new postcards with Science Woman themes. That’s the most immediate. For the past two years I’ve been working on some gouache landscapes of this part of Montana, and I want to do a linoleum print in the same kind of style, to have it available. It’s fine if your work becomes highly desirable, and everybody’s going to pay two million dollars for it, but I would like to think that the average citizen does not have to buy posters to have art in their homes – that they could buy original prints or watercolors, or drawings or whatever. This print would be my move toward that – because the gouache paintings are kind of expensive, because of the huge amount of time they take. If I can, I will do that soon.

When I was in Chicago on this recent train trip, I had about two hours in the Art Institute, and I entered a room I had never seen before, that had a lot of Greek and Minoan pottery. I ended up stopping dead in my tracks, because I have a love of work from that period of time and part of the world. It reminded me very strongly of an art history course I took when I was eighteen and a freshman. It was the most difficult course I took the four years I was in the school – if you had asked me at the time I would have said, boy, it was a mistake to take that class, and yet twenty-five years later, that course stays with me most strongly. Walking into that room at the Institute reminded me, and reawakened my interest in that period. So I rushed down to the public library after I got back, and got out three texts that have color plates of a small amount of pottery, and started a series of paintings that do homage to these primitive pot forms and the spirals, the unusual abstract patterns on the pots. I’m very excited about them. I had to put them aside to get the postcards done, but they’re where my excitement lies right now.

LENNON: You mentioned people owning art. It reminded me of my last trip to the Art Institute. I was also on a train layover. I went in there and saw many famous paintings, and was struck by how precious they were as unique objects – they weren’t a can of Pepsi, they weren’t a bag of potato chips, they were utterly unique! I realized that every piece of art, even if it’s awful, is unique and I think very few people have unique things in their home.

SCIENCE WOMAN: I’m convinced that as our society becomes more and more technologically advanced, and we have people doing things specialized, the art that comes from the simple act of getting an idea and holding a little paintbrush made of sable hairs and applying paint to canvas is very precious. A lot of people don’t value this, they don’t think about it, but to me, it’s one of the most valuable and real activities humans can do!

My parents used to live in Thailand, and when I visited them there about ten years ago, I was enthralled: in Bangkok, probably because of the level of poverty, practically everything was made by hand. The signs were made by hand, the clothes, everything. And – I don’t know if it’s genetic or what – the Thai are very skilled artistically, and it was like bathing in this wonderful environment of tangible imagery. In the United States, everything’s slick and depersonalized. It’s a shame that here, our artists have become specialists, but one of our roles as specialists is to keep that in balance. Otherwise, I think, our culture would suffer dramatically.

LENNON: I sometimes think it has suffered, because of our love of familiar objects. A lot of artists paint what they are expected to paint, what they’ve painted before. Some artists may not be as skilled as others, but maybe if they painted something different they’d discover skills they didn’t know they had. Perhaps if there’s one thing holding contemporary art back, it’s that we feel we have to do something familiar.

SCIENCE WOMAN: I read somewhere generally, in a certain field, you have people who are “worker bees:” those people just kind of do what’s expected of them. The small percentage of people in that field who are actually forging new ground, bringing up new ideas – eventually the worker bees take those ideas and repeat them, put them out into the general population. I don’t think they were talking about artists (they were probably talking about scientists) but I looked at that and thought: it’s true! All the people still doing Charlie Russell paintings in Montanan are not forging new ground. It’s interesting that they’re obsessed with a hundred years ago in the West – an image that didn’t even really exist at the time! – they’re kind of part of the worker bees.

But even in contemporary art, there are people who find something they’re comfortable with, that the public recognizes and will pay them for, and they just…do it! It’s a great way to make a living, whatever. And then you have people who are more willing to try stuff that may not make money for them, and may not be well received initially.

LENNON: I saw a painting of yours that did something with the Montana landscape I’ve never seen before. If I’m not mistaken, it had a glowing car in the middle of a landscape – a talisman for travelers. Anyone who drives in Montana has seen those clusters of crosses by the side of the road marking places where people were killed in accidents. And I thought, there’s something Montana needs, a talisman for driving!

SCIENCE WOMAN: I have about six themes I’m working on, and that’s one of them. I call those “heart’s protection” – it’s the idea of art being a focus – in that particular instance the focus is a car I find particularly charming, a 1950 Chevrolet truck. It was made the same year I was born, and it’s in far worse condition – but we own that truck, and it drives about 10 miles a year. But the thought of a vehicle being protected, so that there’s a kind of locus of protective energy or attention. I love that painting, in a very…charming manner. I’ve done a few other of these paintings, that protect a child, a dog, a family.

But I think it’s interesting – paintings have a very subtle influence. You put it in your house, you probably don’t look at it all the time. In fact, it may only be a few seconds a day, if that. But my belief is that they exert a subtle power in the environment. It is not dependent on you actually making eye contact with it. It’s fun to get into paintings that are specifically to promote that kind of energy.

LENNON: I think that when people are driving, their personal presence vanishes – they forget they exist in the physical world. But in fact, you rarely have a greater physical effect on the world than when you’re driving a car. You’re a rapidly moving, incredibly heavy object!

SCIENCE WOMAN: What was fun for me was, when I went to sketch the truck – and I didn’t grow up with hot rods or anything, I don’t have cars internalized in my personal imagery – I became aware of how beautifully designed it was, and that there’s been a loss in the way that vehicles are presented visually. I think we’re losing something in the way that objects are produced.

LENNON: Let me switch gears. One of the things science is revered for is that it explains the workings of the world. Do you think art can do the same thing? Does it get short shrift because it’s not known for that?

SCIENCE WOMAN: Probably. It’s back to what’s left two thousand years later: statues, buildings. I believe in objects. The theories that come out of scientific progress – if you killed all the humans, that would go away. But, for a time anyway, the relics of our industry and art would survive.

I do see good art as an investigation into the particular time in which we live.In the Caravan, what I found really fulfilling was speaking on behalf of artists. Theoretically, if you have a great painting, that painting should be able to exist independently of what anyone says. But all art is a product of its time – even the cave paintings in France, I love those paintings. They speak well now, but they really were more than what they are now, because they were a product of their time, they had to do with ritual and magic and hunting, and a very different existence by humans. If you remove that context, they may be very pretty and pleasing to the eye, but they lose something. And I think that all art has a subtext, and in some instances artists are conduits to that kind of different intuitive information.

I haven’t done a lot of reading about it, but I know there is information coming out about the way art and the sciences merge – the mystical stuff with physics, where if you carry physics far enough, you get into a very…intuitive perception of the earth and universe.

LENNON: Most of what I know about the world, I probably learned from reading novels. And for awhile I thought: boy, I’m basing my understanding of the world on something imaginary! But increasingly I think there’s nothing more real about top and bottom quarks than there is about a short story or a novel. In a sense, they’re both products of the imagination: in a sense, they’re both very tangible.

SCIENCE WOMAN: And writing can let you into the world of someone’s thoughts. One of the questions you have here is: Is Science Woman a mind reader? I’ve always had a scientific fascination with the fact that you can be sitting across the room from me thinking things that I have no awareness of, unless I am completely intuitive.

LENNON: Recently I had a discussion with a friend via email. We were discussing her personality. And though we were saying things we would have no trouble saying face to face, we got into a heated argument! We couldn’t gauge each other’s reactions and we insulted each other. So we called each other and made up…

SCIENCE WOMAN: Did the phone help? Your voices…

LENNON: I think it did. But it occurred to me: you lose so much without attempting to get into someone’s head. Being able to imagine that is a key to getting along with people.

SCIENCE WOMAN: Exactly. I don’t read minds, but… I actually met my husband, Max, in a psychic awareness class. I do have intuitive abilities, and he does too, yet I made a decision – this was eighteen years ago – not to pursue it. If I had, I’d be the psychic on the local TV station. I wanted to do my art, and turned my back on that. But I think I do that a lot, I pick up subtle clues. It can be to my disadvantage, because other people aren’t doing that, I can get in trouble. But it’s part of the way I operate.

LENNON: I think it disturbs people who don’t use their intuition if you notice something about them and mention it. They get terrified you know something about them that they didn’t necessarily want you to know – even if it’s obvious.

SCIENCE WOMAN: Or they’ll deny it, and tell you you’re wrong. Which is fine: they have autonomy over themselves. No, you don’t always get a warm reception with that kind of stuff.

LENNON: Maybe that’s why art doesn’t always get a warm reception, if good art makes you question yourself. I don’t suppose we want that.

SCIENCE WOMAN: It’s back to iconoclasm. I understand: I don’t want to go through the rebellion! I’m happy with the way things are. It’s uncomfortable to change. One thing that I, as Science Woman, promote, is that people get rid of televisions. I’d like to tell everybody, hey – all televisions, particularly now after the elections, are gone! You don’t get one for a year! The truth of the matter is, most people won’t do that, because they’re in patterns – they come home from work, they have a beer, they put on the television, whatever. As Science Woman, I don’t even pretend I’ll cause a major change in people’s behavior patterns, but maybe there’s some subtle aspect of the message – because of the blatancy of it – that will make somebody think twice.

Before we finish, I want to tell you something: I feel strongly that Science Woman is a role model for young women in particular. I’ve noticed I seem to appeal to young people. In a group, it’s usually the teenagers who get what I’m doing. I’m surprised – under normal circumstances, my art is directed at my peer group, because they’re the ones I’m having the most direct dialogue with, and whose experiences are most similar to mine. But that part is encouraging to me and is also somewhat deliberate. Their role models come out of popular culture, for the most part. They’re sports heroes, TV stars, whatever. My personal bias is that those people are not necessarily the best role models, and that Science Woman’s advantage is authority and age and intelligence, a move away from that popular culture image. I’ve been asked to come to Idaho and do some kind of inspirational talk to a bunch of teenage girls who are having a hard time. I don’t know how much of that is art and how much is missionary. But I appreciate that there is some receptivity to what I’m doing with that group, and it gives me confidence that as they get older, Science Woman will become part of their reality.

I think there are some older people who look at me and think it’s just totally ridiculous.

LENNON: Well, people don’t expect good art to be funny! They expect it to be reverential. But those things aren’t mutually exclusive.

SCIENCE WOMAN: I agree. And it takes a certain amount of confidence to make fun of yourself. If you feel your position is precarious, you want to present that serious façade and have people take you seriously. But at this point, I don’t really care! The more I get out and see what’s going on, the more it reminds me that I can do anything I want, and not to worry about where the audience is. It gives me a great sense of freedom to pursue my own interests. There’s always been a tension: How is the art world looking at this? How do I fit in? And I’m going: Who the hell cares?